Making the Case for Procedural Justice: Is the Current Way of Financing and Supporting Capacity Building for Climate Action Procedurally Unjust?

Capacity building is widely accepted as critical to achieving development outcomes and, more increasingly, as central to addressing challenges exacerbated by the impacts of climate change. There is a consensus that capacity building should be driven by countries’ self-determined needs, with countries having ownership of capacity building processes rather than donors or funders. Among many benefits, country ownership improves the likelihood that capacity-building results are sustainable after donors withdraw.

However, despite the considerable investment in capacity building and the intentions of donors and funders, PlanAdapt would argue that there are many issues with how capacity building is currently funded and how capacity building processes are managed.

The Paris Committee on Capacity-Building (PCCB) is working to address current and emerging gaps and needs in implementing capacity-building in developing countries. They recently issued a Call for Submissions, which PlanAdapt responded to, seeking ‘experiences, good practices and lessons learned related to enhancing the ownership of developing countries of building and maintaining capacity’.

Capacity building is commonly defined as “the process by which individuals, organisations and societies obtain, strengthen and maintain the capabilities to set and achieve their own development objectives over time.” Article 11.2 of the Paris Agreement notes that capacity-building “should be country-driven, based on and responsive to national needs, and foster country ownership of Parties, in particular, for developing country Parties, including at the national, subnational and local levels.” Yet, as the Call for Submissions points out, achieving country ownership within capacity building efforts has been difficult for stakeholders in low-income countries.

While country ownership has been variously defined, it is often related to ensuring effective engagement of national and sub-national stakeholders with projects, decisions and activities. Beyond national institutions, these stakeholders should include local government at the municipal or village-level, the private sector, local communities, academia and civil society organisations, indigenous peoples and women’s organisations. Country ownership of capacity-building is about ensuring that activities are demand-driven and contextually-sensitive, supporting the ‘recipients’ to set their own capacity development agenda, rather than this agenda being externally imposed.

Given that the importance of country ownership and local leadership for effective capacity building is a long established “lesson-learned”, why is it so difficult to put this “best-practice” into effect?

Procedural Injustice in the Way Capacity-Buidling is Financed and Supported?

Our submission argued that the lack of country ownership and local leadership in capacity-building efforts is largely a consequence of the way climate capacity building is financed. We further argued that a failure to focus on the way in which capacity building is financed and supported amounts to ‘procedural injustice’.

Procedural justice is one pillar of climate justice. It is fundamentally about ensuring that decision-making processes are fair, accountable, and transparent, including in the context of responding to climate change through mitigation and adaptation actions. Just procedures are important to regulate the distribution of goods and climate finance and having the transparent and accountable decision-making processes in place. This can include access to information, access to and meaningful participation in decision-making, lack of bias on the part of decision makers, and access to legal procedures. Procedural justice generally focuses on identifying those who plan and make rules, laws, policies, and decisions, and those who are included and can have a say in such processes. Adapted from (Guide on Climate Justice in Gender and Youth Engagement, Oxfam/PlanAdapt, unpublished; IDRC 2020)

Using a climate justice lens to consider the persistent and well-documented shortcomings of current approaches to capacity building can highlight the ways in which procedures and administrative processes, serve to reinforce power asymmetries and act as a barrier to country ownership.

What are the challenges contributing to procedural injustice, and what might procedurla justice look like?

This section is informed by our recent discussion paper: ‘Unleashing the Potential of Capacity Development for Climate Action – Fixing a Broken Link on the Pathway to Transformational Change’ and the extensive experiences of PlanAdapt members.

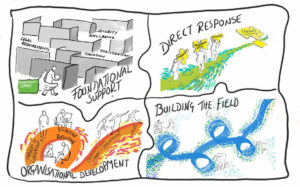

Categorising our thoughts into four key areas, we suggest the following challenges (A-D) which are contributing to procedural injustice in country ownership of capacity-building and outline potential solution areas for each:

Who decides about funding?

Funding for climate-related capacity-building is often governed by norms and practices that can be a barrier to supporting country ownership, such as the tendency to adopt project-based approaches to capacity building. Projects rely on ‘plannable’ outputs, such as discrete outputs like workshops, trainings etc. for which inputs can be monetized and budgeted. Projects necessitate accountability and reporting arrangements which limit flexibility in terms of expenditures, changing of plans and adapting to alternative capacity-building processes. Furthermore, projects tend to employ hierarchical systems of decision-making, which prioritise particular stakeholders, and exclude others.

Potential solution areas

- Project planning should make room for flexible and adaptive management, including an inception phase that allows for uncertainty and co-evolution of activities.

- Outcomes and results that are too narrow and pre-defined should be avoided (see also Solution Area 8 in table 1 of Rokitzki & Hofemeier, 2021).

Who decides about needs?

There is an underlying belief that capacity building is about addressing capacity gaps and needs (often identified in terms of knowledge and skills needed to achieve short term objectives), and a mindset that gaps can be identified and filled by expert providers. People expect supply and expert driven approaches, which creates a barrier to genuine exploration of the range of resources and capabilities needed for individuals, communities, organisations and societies to realise their own goals and ambitions over time. Furthermore, there is an overreliance on skills and knowledge, and negligence of connectivity, respect, trust and relationships as underlying conditions and enablers of capacity building. The application of standardized capacity needs assessments (often defined as skill or knowledge gaps and deficiencies) further perpetuates this.

Potential solution areas

- The role of external experts/outsiders should be more carefully framed. Non-local consultants or experts should not replace national and sub-national experts, but rather act in a role of support, facilitating the process as directed by local actors (see also Solution Area 3 in table 1 of Rokitzki & Hofemeier, 2021).

- There is a need to adjust the overall attitude regarding experts and non-experts within the broader development and climate-aid paradigm. In view of adaptation action, it is necessary to attach greater importance to the experience of locals/practitioners (see also Solution Area 12 in table 1 of Rokitzki & Hofemeier, 2021).

Who decides about the processes?

Agendas of capacity-building processes, including the selection of participants and institutions, are often determined by outsiders (e.g. experts or representatives of funders). Processes are shaped by plans created in the process of securing funding, relying on discrete deliverables like training and workshops often targeting pre-determined themes. Genuinely participatory processes may be slower and generate unpredictable outcomes. Considering the factors enabling or constraining the capacities of individuals or communities may generate demand for activities that do not fit within the typical “capacity building” paradigm.

Potential solution areas

- Capacity should prioritize long-term approaches, enhanced recognition of the period beyond the project end date, and identification of legacy partners, not public administration partners but rather knowledge partners such as universities.

- This relates to the selection of learners, which should be based on self-motivation and interest in professional growth to overcome supply-driven approaches (see also Solution Area 10 in table 1 of Rokitzki & Hofemeier, 2021).

Who defines and evaluates capacity development outcomes?

When measuring success, a key challenge to country-ownership lies in the hands of the measurer. The monitoring and evaluation of projects and the sharing of ‘lessons learned’ and ‘best practices’ are based on unjust procedural biases. Already in the design of indicators, projects are originally designed, funded and implemented by international actors who are inclined towards quantitative, thus measurable outputs. Despite this, there is a clear trend in M&E away from this quantitative focus. Effective measures depend on understanding positive effects of networks, connections and relationships. However, such approaches do not only require enhanced attention and long-term commitment by exogenous funders and implementers, but also a recognition that funds in project budgets need to be set aside to implement them.

Potential solution areas

- Evaluation strategies should enhance the use of existing monitoring, evaluation and results measurement for capacity building. There should be:

- an increased focus on capacity building as an outcome

- better target-setting and understanding/measuring of baselines

- inclusion of new OECD DAC evaluation criteria ‘coherence’

- reflection of intangible outcomes (see also Solution Area 1 in table 1 of Rokitzki & Hofemeier, 2021)

- Examples of robust, qualitative M&E approaches include outcome harvesting, most significant change (MSC), summative evaluation and realist evaluation.

What’s next?

Many of these points are not new; they are well-documented in academia and practice alike, but the alternatives have struggled to be incorporated into project design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation. While there are undoubtedly projects that have demonstrated procedural justice (see FRACTAL and BRACED for example), there are arguably many more projects that perpetuate what we understand to be procedural injustice.

PlanAdapt will continue to practically employ the solution areas highlighted by our Capacity Development Discussion Paper in projects we are involved in and use our influencing ability to advocate for procedural justice in capacity development. We will continue to build alliances and engage with partners to influence how capacity development, particularly in the climate adaptation space, is designed and implemented.

Find out more about our capacity development approach here.

This blog was written by Carys Richards, Catherine Fisher, Martin Rokitzki, Alannah Hofemeier, Anand Menon and Till Groth and Delilah Griswold.